What is Gestalt Therapy?

Gestalt therapy is a phenomenological form of psychotherapy developed by Fritz Perls, Laura Perls and Paul Goodman in the 1940s and 1950s. The theory was first outlined in the 1951 book Gestalt Therapy.

The approach recognises that emotional difficulties can be in the form of emotional and physical reactions.

Because of this, practitioners pay as much attention to the client's Non-Verbal communication as they do to emotional responses.

Key Concepts and Principles of Gestalt Therapy

The central concept of the Gestalt approach is ‘wholeness’ which examines the integrated experiences of clients and relationships with society.

Gestalt therapy focuses on the process, i.e. what is happening, rather than on the content, i.e. what is being discussed.

The goal is for clients to be aware of what they are doing, how they are doing it, and how they can change themselves and learn to accept themselves.

Gestalt therapy synthesizes three philosophies or ‘Pillars of Gestalt’ - phenomenology, field theory, and dialogue.

Phenomenology is a discipline that helps people stand aside from their usual way of thinking so that they can understand what is actually being perceived and felt.

The phenomenological experience of the client is their current or historical background and is called the ‘ground’. From their experience, one element will become figural- the ‘figure’.

Using the concept of figure and ground can explain the process by which people organise their perceptions to create meaning. The ground is mostly out of awareness and different things at different times can become figural.

Field theory underpins the holistic view of the client. There are three types of field which are interconnected:

- experiential field

- relational field

- wider field

The field will be in constant flux so the counsellor needs to keep a flexible focus on what is figural, as well as shuttling between the three fields, to understand how the client is making meaning of the experiences.

The therapeutic relationship needs a working alliance and a dialogic relationship.

In Gestalt, the dialogic relationship is where the therapist is required to bring their whole self to the relational contact to meet the client.

The counsellor needs to be fully present, understanding, validating and authentic, and in doing so practices the following elements: presence, confirmation, inclusion and open communication.

How Does Gestalt Therapy Work?

Awareness is at the centre of the theory and practice of Gestalt therapy.

The Gestalt counsellor will raise the awareness of the client (feelings, thoughts, behaviour, bodily senses) and awareness of how the client makes contact (his relationships with other people, impact on the environment and its impact on him).

The therapy aims to free blocks that inhibit the flow between figure and ground.

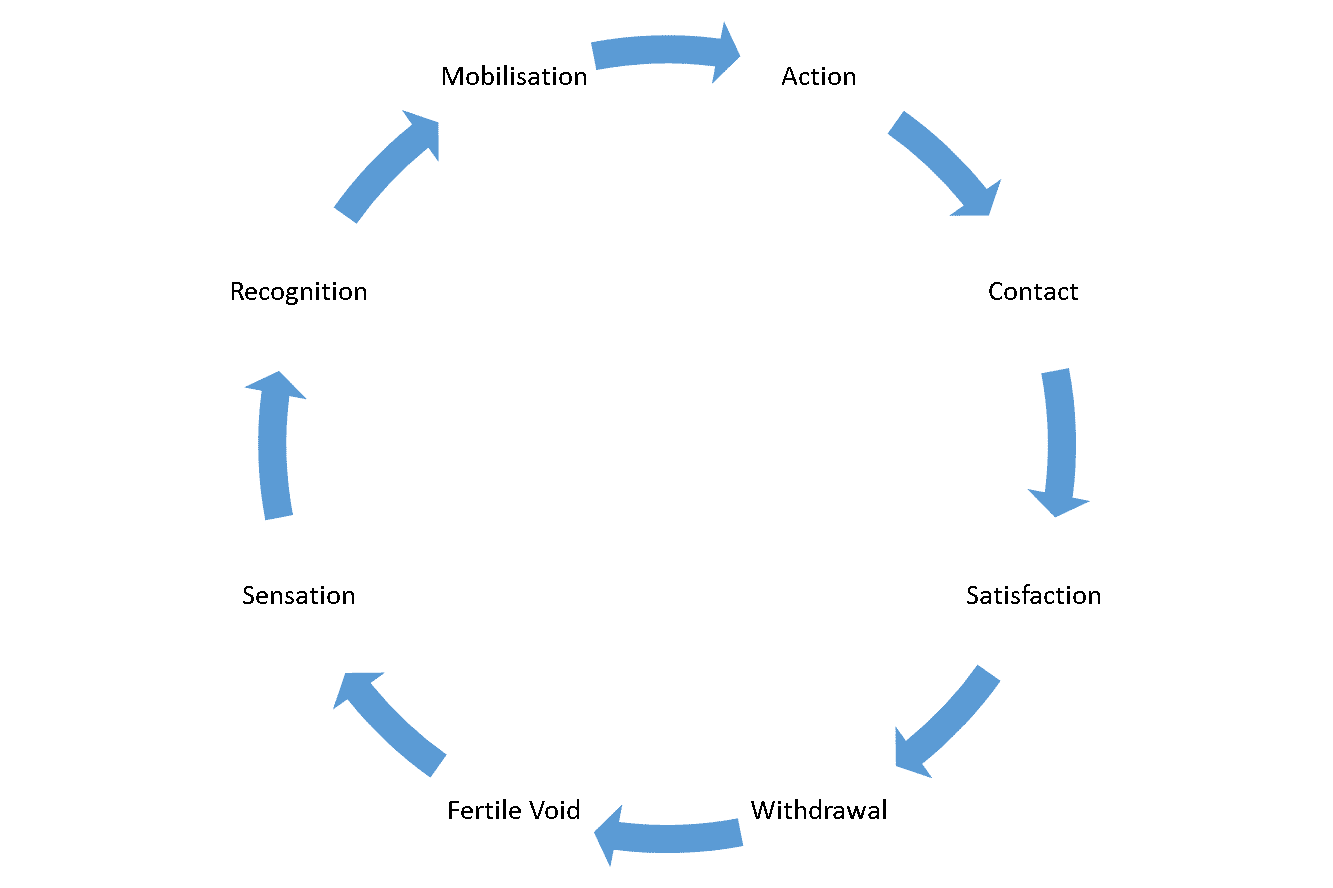

Gestalt therapy uses the ‘cycle of awareness/experience’ to understand the flow of awareness and is a way of tracking the formation, interruption or completion of emerging figures.

This idea of completing and therefore making ‘wholes’ is part of our everyday life and encompasses tasks and our emotional lives.

These life experiences are called ‘gestalts’ which are formed, completed and then formed again as a cycle of experience.

Gestalt therapy believes that humans have a need to make wholes to make sense of our world and therefore complete cycles of experience.

Why is the Cycle of Experience Important?

The cycle of experience identifies the stages from the moment of experiencing a sensation, to being in full contact, to then being ready for a new experience.

The cycle of experience involves the interacting of the whole person with their whole environment. At any one time, a person may go through multiple cycles of experience which are interconnected, and in relation to others and their wants and needs.

Potential gestalts may be halted in order to focus on what is more pressing at the time; where a choice is being made but still living in full present awareness.

Cycle of Experience/Awareness

There may be times when the flow of a gestalt cycle is interrupted or changed, without awareness, which limits the ability to be able to meet a current need in the here and now.

In childhood the experiences that we had, the meanings we made of them and the ways in which we responded to them were often patterns of response that were ‘creative adjustments’ to our world.

The creative adjustment, which was a response to a need at the time, can then become habitual which may not be useful in the present.

As a result, this behaviour may result in a fixed gestalt where behaviour becomes fixed and so much part of ourselves that we become unaware that we are actually choosing them.

Free Handout Download

Paradoxical Theory of Change

Gestalt therapy aims to bring into awareness who we are, how we are living and how we relate to the world around us. Through awareness, we see reality in the present and can make informed choices.

Gestalt therapy believes that humans have a need to make wholes to make sense of our world and therefore complete cycles of experience.

If situations in the past, especially those that have caused trauma, have not been resolved, the gestalt is left incomplete -- this is referred to as ‘unfinished business’.

The unfinished business can leave discomfort in the client as the need has not been met.

This unfinished business can accumulate, and in the extreme can be debilitating and lead to a breakdown of function in daily life.

The counsellor would employ a range of phenomenological enquiries to work with unfinished business depending on its manifestation and severity.

What Attitudes Does the Therapist Adopt?

Working with the client requires the counsellor to adopt an attitude of creative indifference, which means trusting the process of the client and not being attached to any particular outcome.

The counsellor:

- meets the client without preconditions

- surrenders to the relationship

- allows what is figural to surface

- brackets notions of how the client can progress

- fully engage in whichever path the client chooses

Not having a pre-established agenda allows for an existential meeting between two people.

Dialogue from the client may reveal an unexplored theme. A counsellor then might invite the client into a different way of working using an experiment.

Experiments deal with the figural aspect of a person’s situation and can explore a wide range of relational dilemmas.

Co-creating an experiment offers experiential learning for the client and is designed to take the client beyond the familiarity that is their boundary and what is habitual.

The experiment may heighten the client’s awareness of their current situation and how the past may be shaping the here and now.

The counsellor may encourage or use the following:

- Visualisations

- Metaphor

- Art Materials

- Music

Or any other approach that helps the client connect to their inner world.

If it appears that a client is stuck or has unfinished business, two-chair work is a way of amplifying what is on the edge of awareness, polarities, projections, introjections, and top dog/ underdog conflicts.

Experiments can lead to a reconfiguration of the client’s field, and then change can occur in the ground due to awareness that replaces past adjustments.

The paradox is that the more one tries to be who one is not, the more one stays the same ... and that by giving up trying to change, change and growth will occur naturally through a process of ongoing awareness, contact and assimilation.

Free Handout Download

Paradoxical Theory of Change

Gestalt and the 'Paradoxical Theory of Change'

Paradoxical theory of change is at the core of the Gestalt therapy change theory.

The paradox is that the more one tries to be who one is not, the more one stays the same.

The underlying principle is that when people identify with their whole self and acknowledge whatever arises at that moment, the conditions for wholeness and growth are created.

When people do not identify with parts of themselves, inner conflict is created.

Change requires an acceptance of the individual as a whole, including accepting those parts that they would rather disown.

The paradox is that by giving up trying to change, change and growth will occur naturally through a process of ongoing awareness, contact and assimilation.

Written by Annabel Rich