History of Attachment Theory

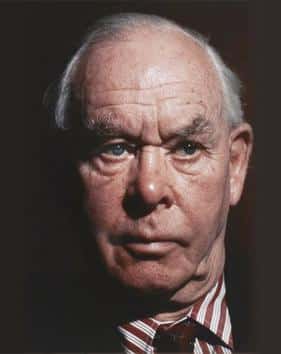

It was British psychiatrist John Bowlby (who worked at the Tavistock Centre, London) who originally introduced the idea of attachment styles at the end of World War II, in the 1950s.

Bowlby was commissioned by the World Health Organization to research what happens when children are taken away at an early age from their mothers (as the war had left many orphans).

Watch this Lecture + Access Hundreds of Hours of CPD

Certified CPD for Qualified Counsellors

- Hundreds of hours of on-demand CPD lectures to help you stay current with your CPD ethical requirements

- Support, and be supported, by thousands of other counsellors as a member of the exclusive online community.

- Access your learning anytime you want ... anywhere you choose ... using any device type — desktop or mobile.

Bowlby concluded that early attachment between infant and mother is essential for normal social development.

One of the criticisms of Bowlby’s work was that he had an over-romanticised view of motherhood – and of course caregivers can be either male or female.

In fact, the government of the time used his conclusions to persuade women to leave their war-time job roles and return to being home-makers, so freeing the jobs for men returning from war.

Attachment Styles

Secure Attachment: ‘I’m OK, you’re OK’

According to the Department for Education, 55% of the population have a secure attachment style. People with a secure attachment style can:

- regulate their own emotions

- understand others’ feelings without fear of rejection

- feel and expect to receive love.

Avoidant Attachment: ‘I’m OK, you’re not OK’

23% of people in the UK struggle to trust others.

The sensation of shame – that they weren’t good enough – can feel overwhelming, leading them to overcompensate and protect themselves in this way.

Other traits in people with this style include:

- thinking before answering questions (again, for self-protection)

- struggling with relationships

- minimising and dismissing their own needs

- being promiscuous

- being controlling

- not taking any risks, through believing the world to be dangerous.

Ambivalent Attachment: 'I’m not OK, you’re OK’

About 8% of the UK population have this attachment style. They need emotional intimacy but they fear it: so you see a ‘push and a pull’.

They may:

- ask for help but then push this away (through fear)

- feel unworthy of love

- become preoccupied with their feelings

- act angrily (as their ‘inner child’ feels ineffective, meaning they can’t regulate their emotions)

They may:

- ask for help but then push this away (through fear)

- feel unworthy of love

- become preoccupied with their feelings

- act angrily (as their ‘inner child’ feels ineffective, meaning they can’t regulate their emotions)

Disorganised Attachment: ‘I’m not OK, you’re not OK’

Around 15% of the population have a disorganised attachment style.

This style can follow experiencing violence or other abuse (activating the amygdala), so that they don’t feel safe in the world.

A natural reaction of a child when threatened is to seek comfort and protection from a caregiver. However, if the caregiver is the abuser, the child finds itself in a paradoxical position trying to elicit comfort from the person who’s abusing them.

People with disorganised attachment are frightened, bear huge physical pain, and can be considered masochistic.

Other common traits include:

- displaying chaotic thinking

- responding angrily to intimacy

- being pulled towards danger

- being unfeeling

- swapping to another therapist without warning, when all seemed to be going well

- being superficially charming and engaging but having psychopathic traits.

Disorganised attachment can sometimes be diagnosed incorrectly as ADHD.

Contributions by Psychologists

Around about the same time, Harry Harlow did some experiments with monkeys, which showed that a stressed baby monkey would choose physical contact over food as a means of comfort.

Later – in the 1970s – Mary Ainsworth (Bowlby’s research assistant) developed a new paradigm, following so-called ‘strange situation experiments’.

These involved a room (observed via one-way glass) full of toys: a mother and baby would enter, the child would play with the toys, a stranger would enter, the mother would walk out, the mother would return, and the stranger would leave.

Ainsworth was able to work out, by the way the child responded, what kind of attachment style they had.

In the 1980s, Mary Main and Judith Solomon extended Bowlby’s and Ainsworth’s ideas, looking at children who had experienced abusive or unresponsive parenting, and coining the term ‘disorganised attachment’.

What Attachment Is

Attachment is an innate biology-driven behaviour in humans, especially infants.

When a child makes eye contact with a caregiver, they feel safe, and it lowers the anxiety hormone, cortisol.

When a child feels threatened, they will generally seek a primary caregiver’s attention.

When the threat is removed, other systems of behaviour are available – meaning that exploration and affiliation can take place.

Differing forms of caregiving can lead to a child developing different views on how much they can trust both themselves and others.

Key Terms in Attachment

- ‘Secure base’ refers to the pace to which a child returns for comfort (usually a parent).

- ‘Proximity maintenance’ describes the tendency in children to keep a caregiver in sight.

- ‘Separation anxiety’ occurs when a child is handed over to someone unfamiliar (or less familiar than their regular caregivers).

- ‘Social referencing’ is where a child looks at a caregiver to see how they should respond.

- ‘Object consistency’ refers to the caregiver’s consistent approach.

Timeline for Attachment

- Attachment may begin even when the child is still in the mother’s womb, with some evidence that babies recognise the voices and sounds they heard at that time.

- Between birth and six months of age, babies develop an attachment to their primary caregiver (who could be female or male).

- By six to 12 months, the child forms a secondary attachment (again, this is not gender-specific).

- By the time a child is five, they have bonded to a family unit.

- Then, they build more significant attachments as they grow older (such as friends, groups and sports teams).

Free Handout Download

Attachment Theory

Factors in Attachment

While neglect and/or abuse in childhood is known to detrimentally affect attachment style, some adults who have been neglected or abused when young do not struggle with attachment.

This may be because they have had another consistent person in their life (such as a teacher, grandparent or neighbour).

Traumatic events (e.g. rape) as an adult can change our attachment style.

Changing Attachment Styles

A positive experience of therapy can help us find – or rediscover – a secure attachment style. This is because brain plasticity allows us to develop new neural pathways.

This may involve the therapist providing what Petruska Clarkson terms ‘re-parenting’.

In other words, if a client has experienced a really neglectful or abusive upbringing, a good therapist may become the attachment object, so allowing consistency: always being there, always taking the same approach, always caring and always showing compassion.

This can help bring about a change of attachment style in our clients as they move through therapy.